CSRF

What is CSRF

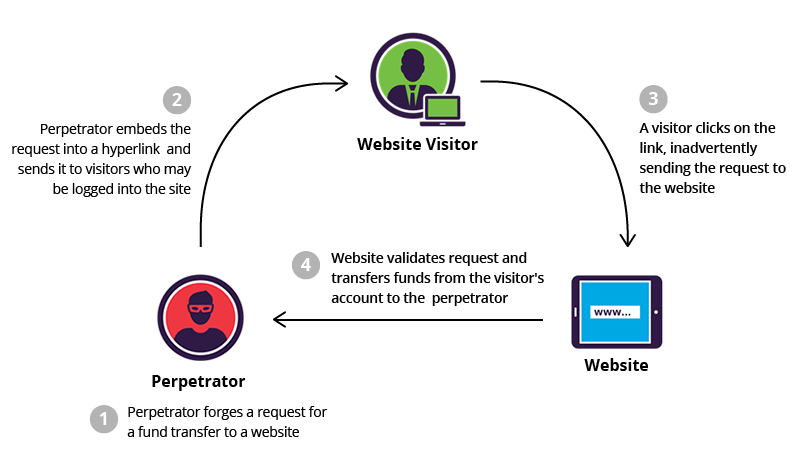

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is a type of attack that occurs when a malicious web site, email, blog, instant message, or program causes a user’s web browser to perform an unwanted action on a trusted site when the user is authenticated.

A CSRF attack works because browser requests automatically include any credentials associated with the site, such as the user’s session cookie, IP address, etc. Therefore, if the user is authenticated to the site, the site cannot distinguish between the forged or legitimate request sent by the victim. We would need a token/identifier that is not accessible to attacker and would not be sent along with forged requests that attacker initiates.

The impact of a successful CSRF attack is limited to the capabilities exposed by the vulnerable application. For example, this attack could result in a transfer of funds, changing a password, or making a purchase with the user’s credentials.

Using social engineering, an attacker can embed malicious HTML or JavaScript code into an email or website to request a specific ‘task URL’. The task then executes with or without the user’s knowledge, either directly or by using a Cross-Site Scripting flaw.

CSRF example

For example, a typical GET request for a $100 bank transfer might look like:

GET http://netbank.com/transfer.do?acct=PersonB&amount=$100 HTTP/1.1A hacker can modify this script so it results in a $100 transfer to their own account. Now the malicious request might look like:

GET http://netbank.com/transfer.do?acct=AttackerA&amount=$100 HTTP/1.1A bad actor can embed the request into an innocent looking hyperlink:

<a href="http://netbank.com/transfer.do?acct=AttackerA&amount=$100">Read more!</a>Next, he can distribute the hyperlink via email to a large number of bank customers. Those who click on the link while logged into their bank account will unintentionally initiate the $100 transfer.

If the bank’s website is only using POST requests, it’s impossible to frame malicious requests using a <a> href tag. However, the attack could be delivered in a <form> tag with automatic execution of the embedded JavaScript.

<body onload="document.forms[0].submit()">

<form action="http://netbank.com/transfer.do" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="acct" value="AttackerA"/>

<input type="hidden" name="amount" value="$100"/>

<input type="submit" value="View my pictures!"/>

</form>

</body>CSRFs are typically conducted using malicious social engineering, such as an email or link that tricks the victim into sending a forged request to a server. As the unsuspecting user is authenticated by their application at the time of the attack, it’s impossible to distinguish a legitimate request from a forged one.

Limitations

The attack is blind: the attacker cannot see what the target website sends back to the victim in response to the forged requests, unless they exploit a cross-site scripting or other bug at the target website.

- The attacker must target either a site that doesn’t check the referrer header or a victim with a browser or plugin that allows referer spoofing.[citation needed]

- The attacker must find a form submission at the target site, or a URL that has side effects, that does something (e.g., transfers money, or changes the victim’s e-mail address or password).

- The attacker must determine the right values for all the forms or URL inputs; if any of them are required to be secret authentication values or IDs that the attacker can’t guess, the attack will most likely fail (unless the attacker is extremely lucky in their guess).

- The attacker must lure the victim to a web page with malicious code while the victim is logged into the target site.

Primary defense technique

Token based mitigation

Synchronizer Token Pattern

Any state changing operation requires a secure random token to prevent CSRF attacks. The CSRF token is added as a hidden field for forms, headers/parameters for AJAX calls (and within the URL if the state changing operation occurs via a GET). The server will rejects the requested action if the CSRF token fails validation.

Inserting the CSRF token in the HTTP request header via JavaScript is considered more secure than adding the token in the hidden field form parameter. In this situation, even if the CSRF token is weak, predictable or leaked but still an attacker cannot forge the POST request directly by setting the custom request header through XMLHttpRequest. When the attacker tries to set any custom header through any XMLHttpRequest, the browser sends the OPTIONS (pre-flight) request, the browser prevents the forged request to be sent.

When a Web application formulates a request, the application should include a hidden input parameter with a common name such as “CSRFToken” (for forms) as header/parameter value for Ajax calls. The value of this token must be randomly generated such that it cannot be guessed by an attacker. Consider leveraging the java.security.SecureRandom class for Java applications to generate a sufficiently long random token. Alternative generation algorithms include the use of 256-bit BASE64 encoded hashes.

<form action="/transfer.do" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="CSRFToken"

value="OWY4NmQwODE4ODRjN2Q2NTlhMmZlYWEwYzU1YWQwMTVhM2JmNGYxYjJiMGI4MjJjZDE1ZDZMGYwMGEwOA==">

</form>Disclosure of Token in URL

Some implementations of synchronizer tokens include the challenge token in GET (URL) requests as well as POST requests. While this control does help mitigate the risk of CSRF attacks, the unique per-session token is being exposed for GET requests. CSRF tokens in GET requests are potentially leaked at several locations:

- browser history

- log files

- network appliances that make a point to log the first line of an HTTP request

- referer headers if the protected site links to an external site.

The ideal solution is to only include the CSRF token in POST requests and modify server-side actions that have state changing affect to only respond to POST requests.

Encryption based Token Pattern

The Encrypted Token Pattern leverages an encryption, rather than comparison method of Token-validation. It is most suitable for applications that do not want to maintain any state at server side.

Server generates a token comprised of the user’s session ID and a timestamp (to prevent replay attacks) using a unique key available only on the server. This token is returned to the client and embedded in a hidden field for forms, in the request-header/parameter for AJAX requests. On receipt of this request, the server reads and decrypts the token value with the same key used to create the token. Once decrypted, If session-id matches and the timestamp is under the defined token expiry time, request can be allowed.

HMAC Based Token Pattern

HMAC Based Token Pattern mitigation is also achieved without maintaining any state at the server. HMAC based CSRF protection works similar to encryption based CSRF protection with a couple of minor differences:

- Use strong HMAC function (SHA256 or stronger algorithms are recommended) instead of an encryption function to generate the token

- Token is HMAC+timestamp

Auto CSRF Mitigation Techniques

Though the technique of mitigating tokens is widely used (stateful with synchronizer token and stateless with encrypted/HMAC token), the major problem associated with these techniques is the human tendency to forget things at times.

To avoid this, you can try to automate the process of adding tokens to CSRF vulnerable resources:

- write wrappers

- write a hook

- use client side script

- in-build framework

Defense In Depth Techniques

Verifying origin with standard headers

At server side we verify if source origin and target origin match, we accept the request as legitimate and if they don’t, we discard the request.

Identifying Source Origin

- If the Origin header is present, verify that its value matches the target origin.

- If the Origin header is not present, verify the hostname in the Referer header matches the target origin.

- If neither of these headers are present, you can either accept or block the request.

In both cases, the target origin check is strong. For example, if your site is site.com make sure site.com.attacker.com does not pass your origin check.

Identifying the Target Origin

If you are behind a proxy, there are a number of options to consider.

- Configure your application to simply know its target origin.

- Use the Host header value.

- Use the X-Forwarded-Host header value.

Double Submit Cookie

If maintaining the state for CSRF token at server side is problematic, an alternative defense is to use the double submit cookie technique. This technique is easy to implement and is stateless. In this technique.

We send a random value in both a cookie and as a request parameter, with the server verifying if the cookie value and request value match. When a user visits the site should generate a pseudorandom value and set it as a cookie on the user’s machine separate from the session identifier. The site then requires that every transaction request include this pseudorandom value as a hidden form value. If both of them match at server side, the server accepts it as legitimate request and if they don’t, it would reject the request.

There’s a belief that this technique would work because a cross origin attacker cannot read any data sent from the server or modify cookie values.

There are a couple of drawbacks associated with the assumptions made here. The problem of “trusting of sub domains and proper configuration of whole site in general to accept HTTPS connections only”.

Samesite Cookie Attribute

SameSite is a cookie attribute (similar to HTTPOnly, Secure etc.) introduced by Google to mitigate CSRF attacks. This attribute helps in preventing the browser from sending cookies along with cross-site requests, possible values are lax or strict.

The strict value will prevent the cookie from being sent by the browser to the target site in all cross-site browsing context, even when following a regular link.

For example, for a GitHub-like website, if a logged-in user follows a link to a private GitHub project posted on a corporate discussion forum or email, GitHub will not receive the session cookie and the user will not be able to access the project.

Though this technique seems to be efficient in mitigating CSRF attacks, it is still in early stages (in draft) and does not have full browser support as mentioned above.

Considering the factors above, it is not recommended to be used as a primary defense. Google agrees with this stance and strongly encourages developers to deploy server-side defenses such as tokens to mitigate CSRF more fully.

Use of Custom Request Headers

An alternate defense that is particularly well suited for AJAX/XHR endpoints is the use of a custom request header. This defense relies on the same-origin policy (SOP) restriction that only JavaScript can be used to add a custom header, and only within its origin. By default, browsers do not allow JavaScript to make cross origin requests.

User Interaction Based CSRF Defense

It’s easier or more appropriate to involve the user in the transaction to prevent unauthorized operations:

- Re-Authentication (password or stronger)

- One-time Token

- CAPTCHA

For applications that are in need of high security for some operations. Please note that tokens by themselves can mitigate CSRF, developers should use these techniques only to achieve additional security for their high sensitive operations.

Not So Popular CSRF Mitigations

- Triple Submit Cookie

- Content-Type Header Validation

Resources

CSRF Attacks: Anatomy, Prevention, and XSRF Tokens - acunetix

Cross site request forgery (CSRF) attack - imperva

Cross-site request forgery - wikipedia